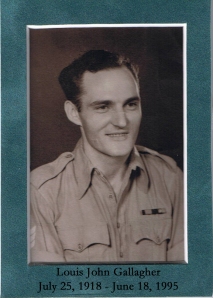

When the war came, my father set out to find it. He was living across the ocean in what was to become my homeland. But the war was important, he told me once. Britain was his homeland and all the young men were going. He figured he’d be okay. So off he went.

When the war came, my father set out to find it. He was living across the ocean in what was to become my homeland. But the war was important, he told me once. Britain was his homeland and all the young men were going. He figured he’d be okay. So off he went.

It was a lie. Not just the one he told about his age, but the other, bigger one, about being okay. The war did not sit well with my father. Not then, and not in years to come.

My father seldom mentioned the war. He never spoke of what he saw, the things that hurt him, the regrets and sorrows he carried, the things he learned and wished he hadn’t. It was as if in the silencing of the guns, memory had to be silenced too.

I wondered about his memories. I wondered if that was where his anger came from. He wasn’t a violent man, my father, but he was mercurial. One moment the world would be sunny and bright, the next a dark and seething storm would erupt and all you could do to avoid it was run for cover. I wondered if it was his unspoken memories that pushed him over the edge into darkness. I wondered if in not speaking of what happened, the pain could find no release except through anger.

Over the years, my father’s anger waned. Over the years, the memories he never spoke of dimmed too. I wonder if his anger would never have come home if he had found peace with memory.

This is a reprint of a post from my Recover Your Joy blog. I share it on Remembrance Day in honour of my father, and all the poet boys who never found peace when the guns were silenced because when they came home, they could not forget.

The Poet Boy

When the poet boy was sixteen, he lied about his age and ran off to war. It was a war he was too young to understand. Or know why he was fighting. When the guns were silenced and the victors and the vanquished carried off their dead and wounded, the poet boy was gone. In his stead, there stood a man. An angry man. A wounded man. The man who would become my father.

When the poet boy was sixteen, he lied about his age and ran off to war. It was a war he was too young to understand. Or know why he was fighting. When the guns were silenced and the victors and the vanquished carried off their dead and wounded, the poet boy was gone. In his stead, there stood a man. An angry man. A wounded man. The man who would become my father.

By the time of my arrival, the final note in a quartet of baby-boomer children, the poet boy was deeply buried beneath the burden of an unforgettable war and the dark moods that permeated my father’s being with the density of storm clouds blocking the sun. Occasionally, on a holiday or a walk in the woods, the sun would burst through and signs of the poet boy would seep out from beneath the burden of the past. Sometimes, like letters scrambled in a bowl of alphabet soup that momentarily made sense of a word drifting across the surface, images of the poet boy appeared in a note or a letter my father wrote me. For that one brief moment a light would be cast on what was lost and then suddenly, with the deftness of a croupier sweeping away the dice, the words would disappear as the angry man came sweeping back with the ferocity of winter rushing in from the north.

I spent my lifetime looking for the words that would make the poet boy appear, but time ran out when my father’s heart gave up its fierce beat to the silence of eternity. It was a massive coronary. My mother said he was angry when the pain hit him. Angry, but unafraid. She wasn’t allowed to call an ambulance. She wasn’t allowed to call a neighbor. He drove himself to the hospital and she sat helplessly beside him. As he crossed the threshold of the emergency room, he collapsed, never to awaken again. In his death, he was lost forever, leaving behind my anger for which I had no words.

On Remembrance Day, ten years after his death, I went in search of my father at the foot of the memorial to an unnamed soldier that stands in the middle of a city park. A trumpet played “Taps”. I stood at the edge of the crowd and fingered the felt of the bright red poppy I held between my thumb and fingers. It was a blustery day. A weak November sunshine peeked out from behind sullen grey clouds. Bundled up against the cold, the crowd, young and old, silently approached the monument and placed their poppies on a ledge beneath the soldier’s feet.

I stood and watched and held back.

I wanted to understand the war. I wanted to find the father who might have been had the poet boy not run off to fight “the good war” as a commentator had called it earlier that morning on the radio. Where is the good in war, I wondered? I thought of soldiers falling, mother’s crying and anger never dying. I thought of the past, never resting, always remembered and I thought of my father, never forgotten. The poet boy who went to war and came home an angry man. In his anger, life became the battlefield upon which he fought to retain some sense of balance amidst the memories of a world gone mad.

Perhaps it is as George Orwell wrote in his novel, Nineteen Eighty-four:

“The very word ‘war’, therefore, has become misleading. It would probably be accurate to say that by becoming continuous war has ceased to exist… War is Peace.”

For my father, anger became the peacetime of his world until his heart ran out of time and he lost all hope of finding the poetry within him.

There is still time for me.

On that cold November morning, I approach the monument. I stand at the bottom step and look at the bright red poppies lining the gun metal grey of the concrete base of the statue. Slowly, I take the first step up and then the second. I hesitate then reach forward and place my poppy amongst the blood-red row lined up along the ledge.

I wait. I don’t want to leave. I want a sign. I want to know my father sees me.

I turn and watch a white-haired grandfather approach, his gloved right hand encasing the mitten covered hand of his granddaughter. Her bright curly locks tumble from around the edges of her white furry cap. Her pink overcoat is adorned with little white bunnies leaping along the bottom edge. She skips beside him, her smile wide, blue eyes bright.

They approach the monument, climb the few steps and stop beside me. The grandfather lets go of his granddaughter’s hand and steps forward to place his poppy on the ledge. He stands for a moment, head bowed. The little girl turns to me, the poppy clasped between her pink mittens outstretched in front of her.

“Can you lift me up?” she asks me.

“Of course,” I reply.

I pick her up, facing her towards the statue.

Carefully she places the poppy in the empty spot beside her grandfather’s.

I place her gently back on the ground.

She flashes me a toothy grin and skips away to join her grandfather where he waits at the foot of the monument. She grabs his hand.

“Do you think your daddy will know which one is mine?” she asks.

The grandfather laughs as he leads her back into the gathered throng.

“I’m sure he will,” he replies.

I watch the little girl skip away with her grandfather. The wind gently stirs the poppies lining the ledge. I feel them ripple through my memories of a poet boy who once stood his ground and fell beneath the weight of war.

My father is gone from this world. The dreams he had, the promises of his youth were forever lost on the bloody tide of war that swept the poet boy away. In his passing, he left behind a love of words borne upon the essays and letters he wrote me throughout the years. Words of encouragement. Of admonishment. Words that inspired me. Humored me. Guided me. Touched me. Words that will never fade away.

I stand at the base of the monument and look up at the soldier mounted on its pedestal. Perhaps he was once a poet boy hurrying off to war to become a man. Perhaps he too came back from war an angry man fearful of letting the memories die lest the gift of his life be forgotten.

I turn away and leave my poppy lying at his feet. I don’t know if my father will know which is mine. I don’t know if poppies grow where he has gone. But standing at the feet of the Unknown Soldier, the wind whispering through the poppies circling him in a blood-red river, I feel the roots of the poet boy stir within me. He planted the seed that became my life.

Long ago my father went off to war and became a man. His poetry was silenced but still the poppies blow, row on row. They mark the place where poet boys went off to war and never came home again.

The war is over. In loving memory of my father and those who fought beside him, I let go of anger. It is time for me to make peace.

Today I think of my Uncle Guerard De Nancrede. He was my hero as a young boy. Pilot, father, brother, uncle, grandfather and rakish good looking guy whom I believe never could find anything in his after WW2 life to compare with the experience of being at war. Like you imply, being at war with an enemy, often times yourself in a prisoner of war camp of memory, is a horrid price to pay for doing the “right thing” even if it is not the “right thing”. Ambiguous words for an ambiguous struggle.

I PRAY FOR REAL PEACE FOR ALL MEN AND WOMEN.

Namaste

John

LikeLike

I so agree John — the ambiguity of the struggle, of the right thing of doing what is not the right thing for humanity. And what we are left with, what it creates more of, what scars it leaves and opens.

And can I just say… I love your uncle’s name! He sounds rakish! 🙂 It is also something I noticed yesterday, how for those who fought, the memories are often not about the fighting — those they try to forget — what they hold onto is the camaraderie, the excitement, the challenge, the ‘kill or be killed’ spirit.

Namaste to you my friend.

LikeLike

Dad would have been so very proud of you for writing so beautifully and for this tribute on Remembrance Day. I believe that he was proud of all of his children during his lifetime and oftentimes he wasn’t able to express himself verbally but only with the written word. I, too, have a few treasured letters written by his hand. He seldom spoke of his war time years and I suspect, like so many other veterans, that he held many untold stories in his heart. Perhaps they were too painful to tell? Thank-you Louise. Lots of Love from your older sis, Jackie

LikeLike

Love and hugs to you too Jackie! Blessings.

LikeLike

Wow. Why does that world alway pop up with you? And why do I ALWAYS read to the end of everything you write? Not that I ever “LIKE” anything I truly don’t like but I don’t read everything I don’t bother clicking on. I do always with yours.

My Great Uncle was lost in the war. He was my grandma’s baby brother. She was so sad; she always talked about him. War is a horrible thing. My Step dad lied about his age and joined the airforce just to eat. He was so poor. How sad. He is the kindest man I know and yet has a temper… I wonder… I never thought to ask him about the war.

I think we can all be codependentents in some way. I know mine caused me to allow my abuse. It was my way of finding something broken and trying to fix it. Who knows why we stayed…. but anger that we cannot control is like black magic… whether it is ours or someone else’s.

This really made me think.

Thank you for sharing. Thank you for always sharing pieces of you. I feel I get to know somebody special when I keep getting glimpses!

xoxo

LikeLike

Oh my Di — “anger that we cannot control is like black magic… whether it is ours or someone else’s.” — now I get to say “Wow!” Powerful words and so true. Thank you!

LikeLike

Just beautiful! xx

LikeLike

Thank you Liz! xx

LikeLike

Amazing post, Louise. Thank you.

LikeLike

🙂 You’re welcome Ann.

LikeLike

Pingback: Day 316: Letting Go of Anger | The Year of Living Non-Judgmentally

My grandfather (my mother’s father) got lost in WW1 in a similar manner. My own dad survived WW2, although he never spoke of it.

Great post and the message at the end of letting go of anger is an important one for all of us.

LikeLike

Louise, it really appreciate your piece in remembrance. I have heard of many soldiers that would not talk about their horrific experiences. Our soldiers of today as well have experienced some horrific things during their role to support Canada in Bosnia, Croatia, peace keeping duties, and now Afghanistan. We need to continue to lobby our government to provide the needed support to our troops, past and present rather than closing the DVA offices across Canada. My brother Captain Shane Fowler just retired in w2013 with serving 35 years including Afghanistan. We all need to pray for peace within their minds and this tragic world,

LikeLike

Sharon, thank you for your thoughtful and compassionate response. You are right — we must put pressure on our governments to do the right thing. Blessings to you Sharon. It is lovely to hear from you. Thank you.

LikeLike