In Canada, National Indigenous History Month reminds each of us of our responsibility, individually and collectively, to create change, to build better, to open our hearts and minds so that Indigenous Peoples know their stories are heard, their history not forgotten and their cries for justice, equality and belonging are heeded.

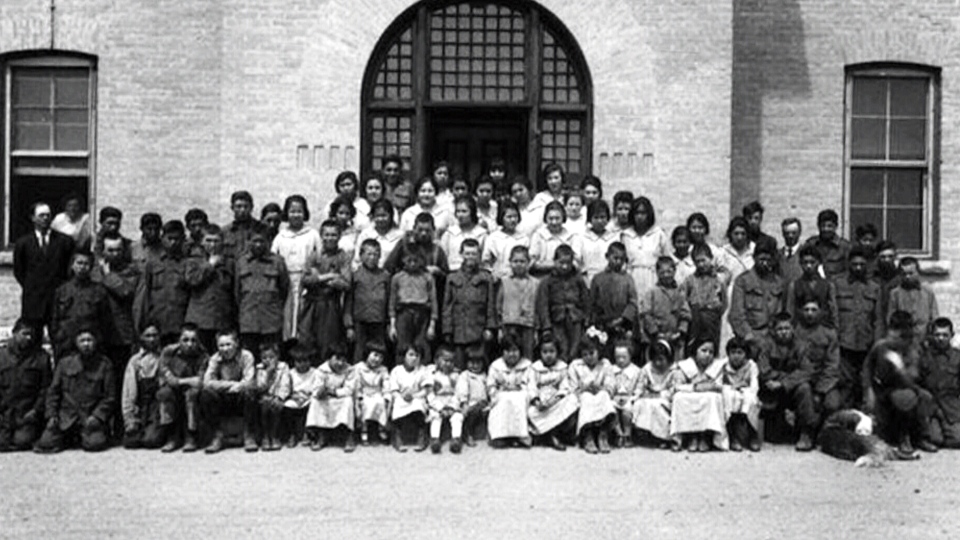

Last year, the news of 215 remains found at the former Kamloops Residential School on the lands of the Tk’emlups te Secwepemc First Nation, rocked the nation.

Like so many, I grappled with how to make sense of it all. I struggled to find ways to not only understand, but to figure out my role in reconciliation.

We all have a role to play in reconciliation. For me, it’s about learning more without letting the burden of all that was done to destroy the lives, culture, beliefs and rights of Indigenous Peoples, and all that is wrong today, draw me back into denial. It’s about creating space in my heart and mind for truth to illuminate my desire to ‘not know’ so that I can fearlessly see into the darkness of what was done to Indigenous peoples that created my privilege today. And in that seeing, take action to break down stigma, speak out against discrimination and racism and create better for everyone.

As part of my journey, I wrote this poem after hearing the news of 215 remains found at Tk’emlups te Secwepemc. I share it again this year to remind me there is still much to be done and much I can do.

Did They Search For The Children? by Louise Gallagher When they discovered they were gone, when they realized their bed was empty did they search for the children? Did they send out a call for volunteers to come band together with the police and school administrators and community members and the parents whose tears could not stop falling as they searched desperately the long tall grasses that surrounded the school in a frantic attempt to find their child gone missing in the night. Did they search or did they already know it was too late the child was gone forever buried beneath the black earth covering their tiny, fragile body still forever more. And when the mother came knocking, knocking, knocking at the door her body awash in a river of pain did they bring her inside and wrap their arms around her and tell her how, how this had happened what had gone wrong how sorry and ashamed and horrified they were that her child was lost and that they too would never stop searching for answers never stop searching for her child forever more. Or did they slam the door laughing at her dirty Indian face leaving her to wander inconsolably in the rain and the sleet and the snow under a hot burning sun along the long dusty road leading away from the last known place where she had seen her child enter that dark day the police and the Indian Agent had come to steal her child away. Did they slam the door in her face? Did they turn their backs on the mother and whisper amongst themselves how they would never tell anyone what had happened to the child. These questions these remains these stories of two hundred and fifteen children found buried deep beneath the black soil surrounding a school where children were taken from their loving families so the ‘Indian’ could be beaten out of them, these questions these remains these stories they haunt me. And I imagine a mother grasping for her child as the police tear the wee one out of her arms and I see Auschwitz and Buchenwald but I do not see my Canada Oh my Canada we have lived with these stories burning deep buried beneath the dark soils of this land eating away at our nationhood and still we do little. And I imagine it happening to me while my daughters were young or my daughter’s children and the children of her friends right now being forcibly taken so the Canadian can be beaten out of them and I wonder would we ever recover? Would we ever get over it as so many suggest those who lost their children and their culture and their language and their land must do now? And I wonder can we ever recover from our past? Can we ever wash away our shame when we know now, as they knew then, we cannot bring these children back. They are gone forever.

I am at a dinner party. The people around the table are all successful by society’s norms. They have achieved status, good jobs, make contributions to their organizations, families, communities, society.

I am at a dinner party. The people around the table are all successful by society’s norms. They have achieved status, good jobs, make contributions to their organizations, families, communities, society.